Not Just Canadian Bacon

Believe it or not, both the United States and Canada have already thought about what war with the other would look like

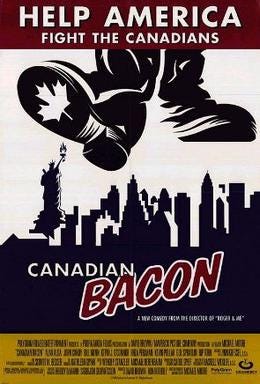

In the 1995 Michael Moore1 movie Canadian Bacon, a struggling U.S. President is persuaded by his advisors to get into a war with Canada.

In South Park: Bigger, Longer, & Uncut, the United States and Ca…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Duckpin to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.